Drexel professor Yury Gogotsi, working with a doctoral candidate visiting from Tsinghua University (Beijing), discovered the method. But getting Samsung and the myriad other Li-ion battery producers and OEMs to sign on to the concept has proved more difficult than confirming that the nanodiamond additive works.  “We had to use internal funding from Drexel to even prove the concept,” Gogotsi told EE Times. “Now we are still trying to attract industrial partners to fund us to characterize the process in more detail and to determine exactly how much nanodiamond needs to be added to the electrolyte in particular applications.”

“We had to use internal funding from Drexel to even prove the concept,” Gogotsi told EE Times. “Now we are still trying to attract industrial partners to fund us to characterize the process in more detail and to determine exactly how much nanodiamond needs to be added to the electrolyte in particular applications.”

It’s possible that the “diamond” in nanodiamond is putting off cost-conscious manufacturers, as Li-ion battery technology already is expensive. But that concern is unfounded, Gogotsi said, since nanodiamonds are cheap to manufacture and, in fact, can be created from waste materials.

“All you need to do is take expired explosives, which are otherwise expensive to dispose of, and explode them in a sealed chamber,” Gogotsi said. “The result will be a coating on the walls of the chamber that is more than 50 percent nanodiamonds typically measuring just 5 nanometers across.”

The mechanism, believe it or not, is analogous to the way Superman made diamonds in the comic books: The superhero applied incredibly high pressure to ordinary carbon, forcing it into its most compact structure. Of course, the Man of Steel used his bare hands, whereas Gogotsi’s method depends on the incredible pressures created by an explosion in a closed space.

Gogotsi’s lab uses but “did not create” the process for creating nanodiamonds, he said. “In fact, it was invented by three separate laboratories in Russia and was kept so secret that each lab was unaware of the other labs’ similar discovery.”

Los Alamos National Lab eventually published a description of the process, which today is used worldwide to turn hard-to-dispose-of waste — such as expired C4 — into marketable products. Nanodiamonds are widely used today in such products as industrial abrasives, medical coatings, and electronic sensors that measure magnetic fields.

Now nanodiamonds are poised to solve the igniting-battery problem that killed off the Galaxy Note 7 — if manufacturers can be convinced to use them.

Source: https://www.eetimes.com/document.asp?doc_id=1332526

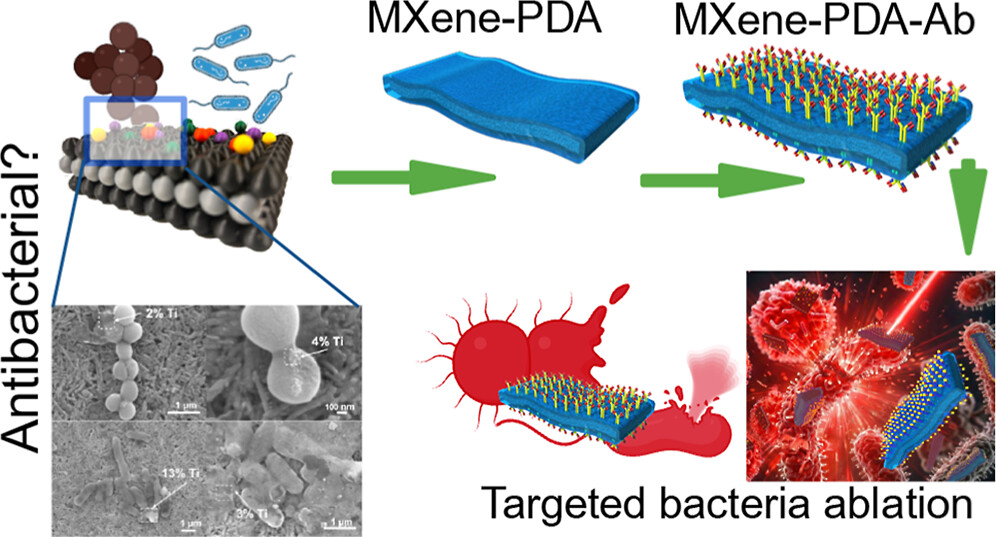

Do MXene nanosheets possess intrinsic antibacterial activity? A systematic study of high-quality Ti-, V-, and Nb-based MXenes reveals negligible inherent antimicrobial effects while highlighting their strong potential for targeted photothermal antibacterial therapy.

Do MXene nanosheets possess intrinsic antibacterial activity? A systematic study of high-quality Ti-, V-, and Nb-based MXenes reveals negligible inherent antimicrobial effects while highlighting their strong potential for targeted photothermal antibacterial therapy. Highlights

Highlights We are excited to share that our Carbon-Ukraine (Y-Carbon LLC) company participated in the I2DM Summit and Expo 2025 at Khalifa University in Abu-Dhabi! Huge thanks to Research & Innovation Center for Graphene and 2D Materials (RIC2D) for hosting such a high-level event.It was an incredible opportunity to meet brilliant researchers and innovators working on the next generation of 2D materials. The insights and energy from the summit will definitely drive new ideas in our own development.

We are excited to share that our Carbon-Ukraine (Y-Carbon LLC) company participated in the I2DM Summit and Expo 2025 at Khalifa University in Abu-Dhabi! Huge thanks to Research & Innovation Center for Graphene and 2D Materials (RIC2D) for hosting such a high-level event.It was an incredible opportunity to meet brilliant researchers and innovators working on the next generation of 2D materials. The insights and energy from the summit will definitely drive new ideas in our own development. Carbon-Ukraine team had the unique opportunity to visit XPANCEO - a Dubai-based deep tech startup company that is developing the first smart contact lenses with AR vision and health monitoring features, working on truly cutting-edge developments.

Carbon-Ukraine team had the unique opportunity to visit XPANCEO - a Dubai-based deep tech startup company that is developing the first smart contact lenses with AR vision and health monitoring features, working on truly cutting-edge developments. Our Carbon-Ukraine team (Y-Carbon LLC) are thrilled to start a new RIC2D project MX-Innovation in collaboration with Drexel University Yury Gogotsi and Khalifa University! Amazing lab tours to project collaborators from Khalifa University, great discussions, strong networking, and a wonderful platform for future collaboration.

Our Carbon-Ukraine team (Y-Carbon LLC) are thrilled to start a new RIC2D project MX-Innovation in collaboration with Drexel University Yury Gogotsi and Khalifa University! Amazing lab tours to project collaborators from Khalifa University, great discussions, strong networking, and a wonderful platform for future collaboration.

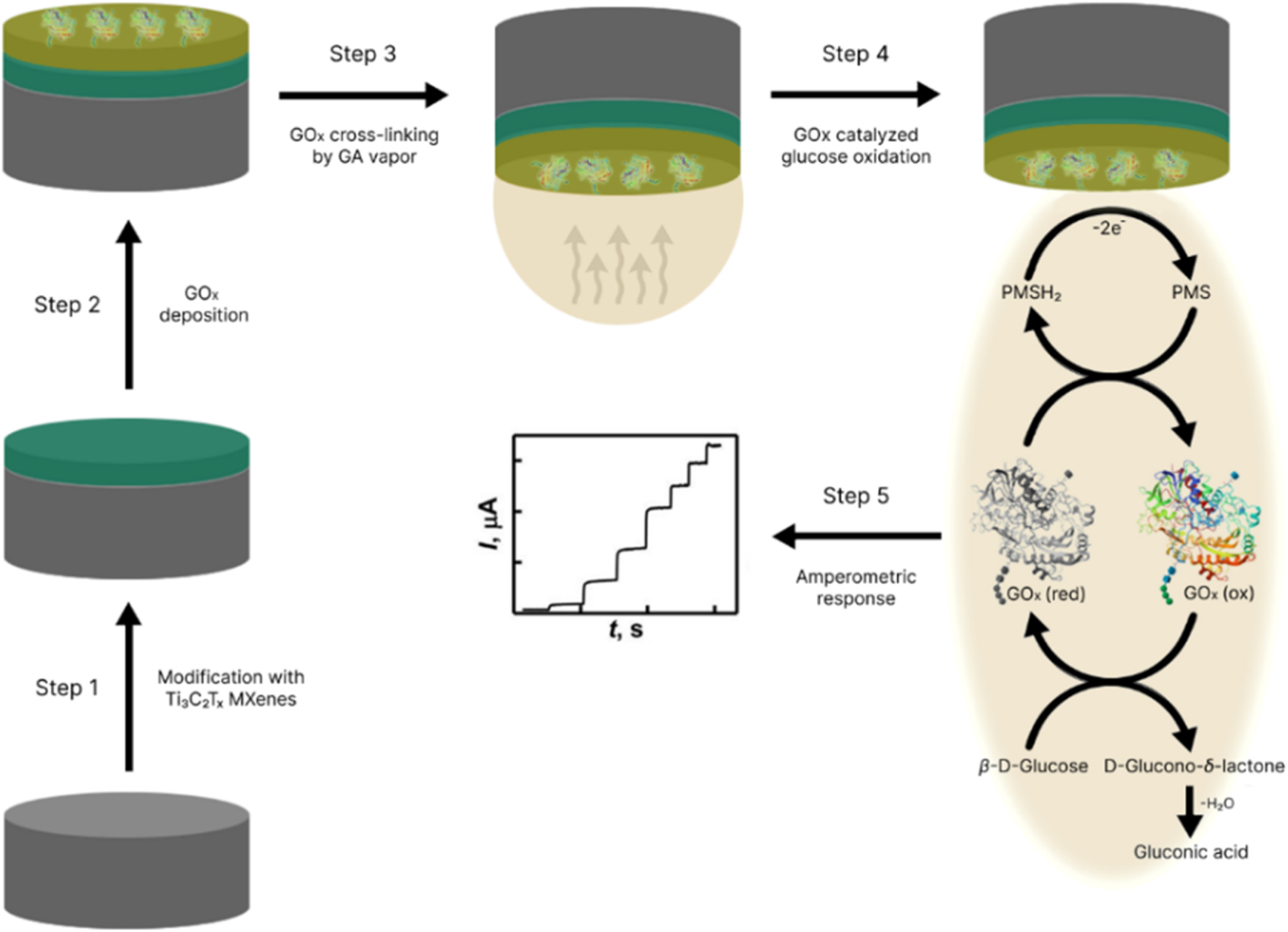

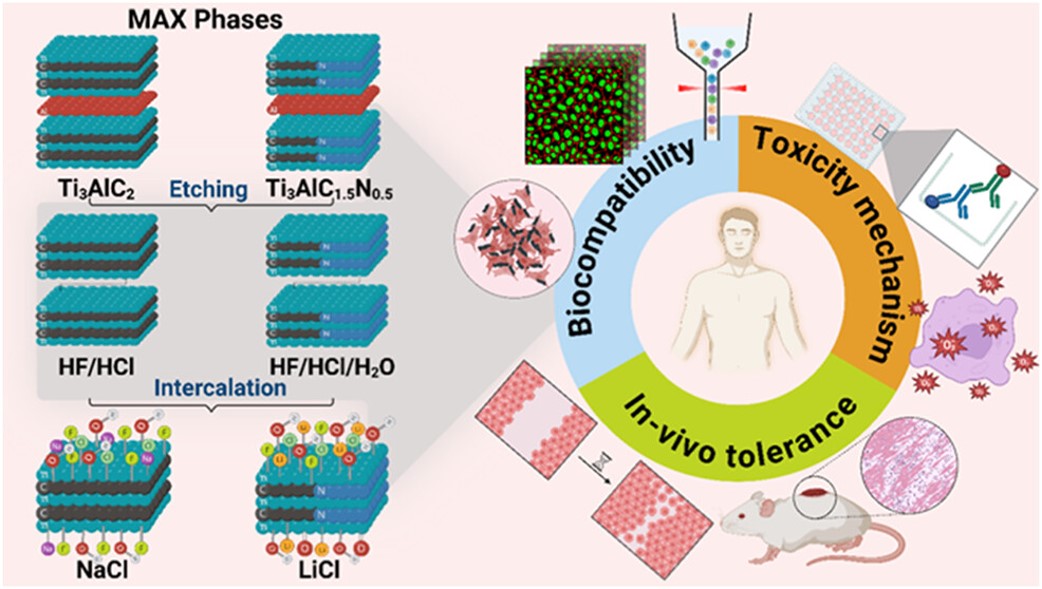

MXenes potential applications include sensors, wound healing materials, and drug delivery systems. A recent study explored how different synthesis methods affect the safety and performance of MXenes. By comparing etching conditions and intercalation strategies, researchers discovered that fine-tuning the surface chemistry of MXenes plays a crucial role in improving biocompatibility. These results provide practical guidelines for developing safer MXenes and bring the field one step closer to real biomedical applications.

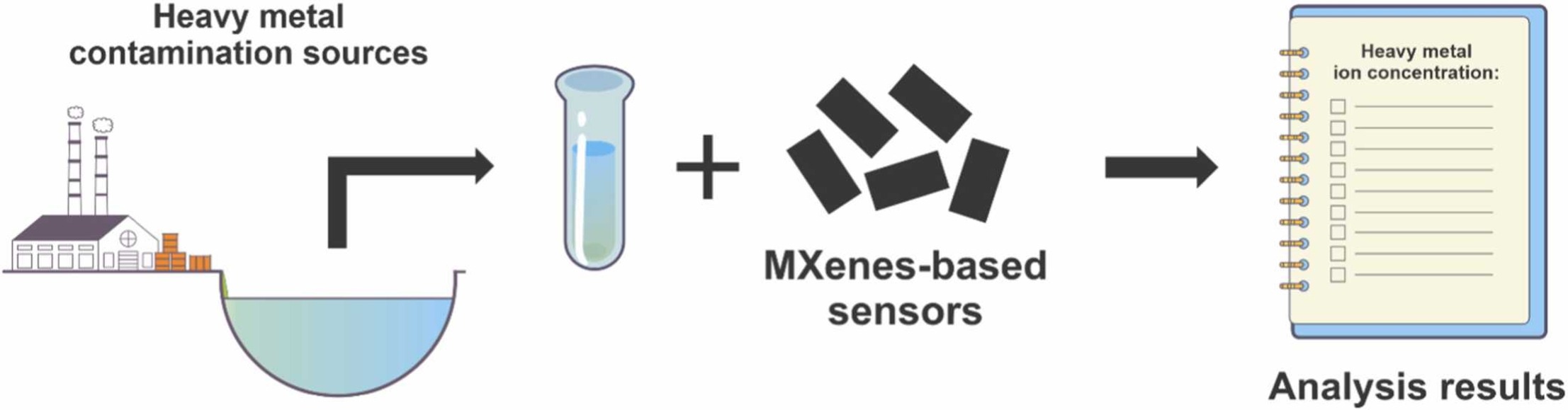

MXenes potential applications include sensors, wound healing materials, and drug delivery systems. A recent study explored how different synthesis methods affect the safety and performance of MXenes. By comparing etching conditions and intercalation strategies, researchers discovered that fine-tuning the surface chemistry of MXenes plays a crucial role in improving biocompatibility. These results provide practical guidelines for developing safer MXenes and bring the field one step closer to real biomedical applications. An excellent review highlighting how MXene-based sensors can help tackle one of today’s pressing environmental challenges — heavy metal contamination. Excited to see such impactful work moving the field of environmental monitoring and sensor technology forward!

An excellent review highlighting how MXene-based sensors can help tackle one of today’s pressing environmental challenges — heavy metal contamination. Excited to see such impactful work moving the field of environmental monitoring and sensor technology forward!

Carbon-Ukraine team was truly delighted to take part in the kickoff meeting of the ATHENA Project (Advanced Digital Engineering Methods to Design MXene-based Nanocomposites for Electro-Magnetic Interference Shielding in Space), supported by NATO through the Science for Peace and Security Programme.

Carbon-Ukraine team was truly delighted to take part in the kickoff meeting of the ATHENA Project (Advanced Digital Engineering Methods to Design MXene-based Nanocomposites for Electro-Magnetic Interference Shielding in Space), supported by NATO through the Science for Peace and Security Programme. Exellent news, our joint patent application with Drexel University on highly porous MAX phase precursor for MXene synthesis published. Congratulations and thanks to all team involved!

Exellent news, our joint patent application with Drexel University on highly porous MAX phase precursor for MXene synthesis published. Congratulations and thanks to all team involved! Our team was very delighted to take part in International Symposium "The MXene Frontier: Transformative Nanomaterials Shaping the Future" – the largest MXene event in Europe this year!

Our team was very delighted to take part in International Symposium "The MXene Frontier: Transformative Nanomaterials Shaping the Future" – the largest MXene event in Europe this year!  Last Call! Have you submitted your abstract for IEEE NAP-2025 yet? Join us at the International Symposium on "The MXene Frontier: Transformative Nanomaterials Shaping the Future" – the largest MXene-focused conference in Europe this year! Final Submission Deadline: May 15, 2025. Don’t miss this exclusive opportunity to showcase your research and engage with world leaders in the MXene field!

Last Call! Have you submitted your abstract for IEEE NAP-2025 yet? Join us at the International Symposium on "The MXene Frontier: Transformative Nanomaterials Shaping the Future" – the largest MXene-focused conference in Europe this year! Final Submission Deadline: May 15, 2025. Don’t miss this exclusive opportunity to showcase your research and engage with world leaders in the MXene field! We are excited to announce the publication of latest review article on MXenes in Healthcare. This comprehensive review explores the groundbreaking role of MXenes—an emerging class of 2D materials—in revolutionizing the fields of medical diagnostics and therapeutics. Read the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR04853A.

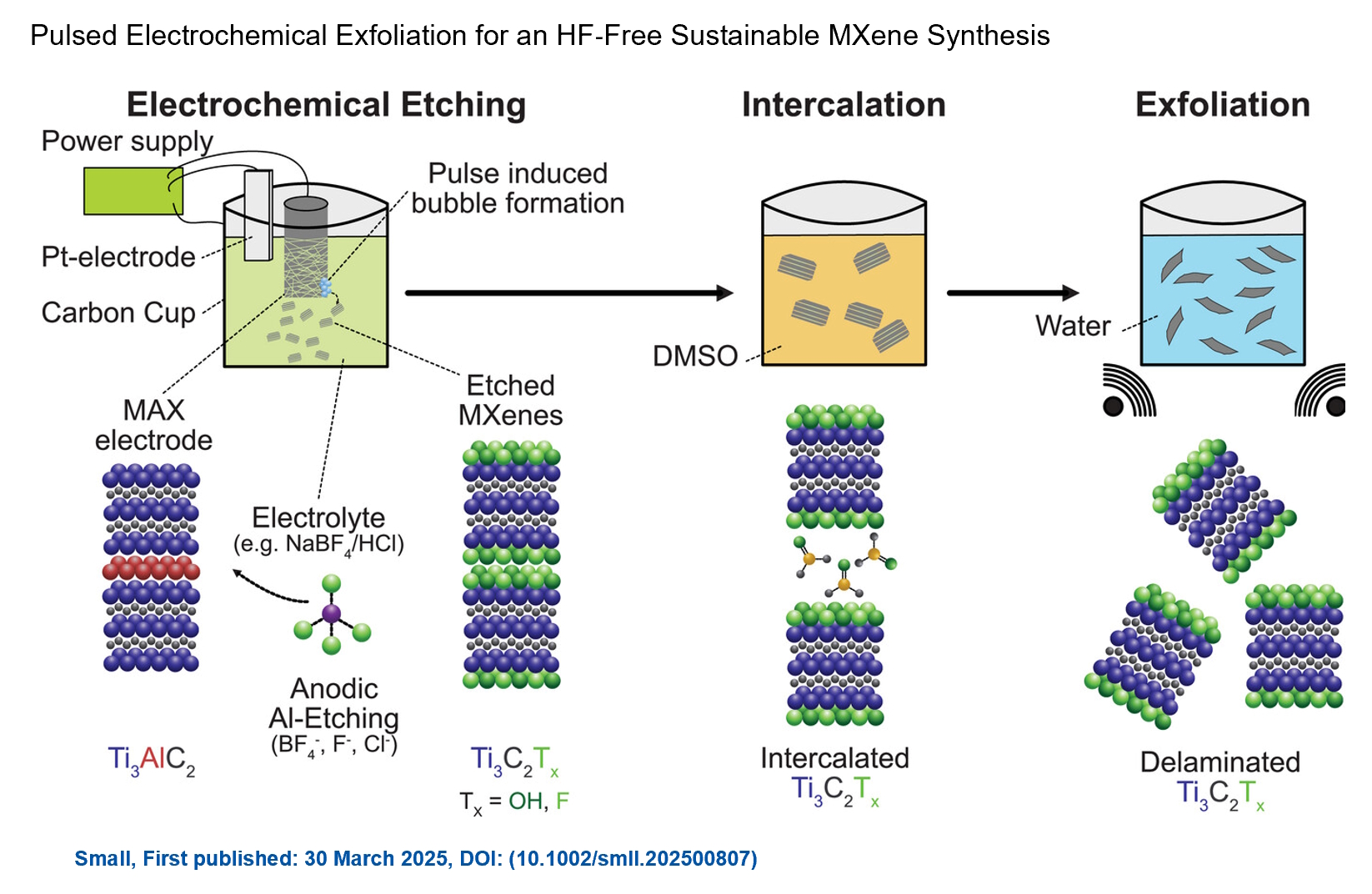

We are excited to announce the publication of latest review article on MXenes in Healthcare. This comprehensive review explores the groundbreaking role of MXenes—an emerging class of 2D materials—in revolutionizing the fields of medical diagnostics and therapeutics. Read the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR04853A. Congratulations and thank you to our collaborators from TU Wien and CEST for very interesting work and making it published! In this work, an upscalable electrochemical MXene synthesis is presented. Yields of up to 60% electrochemical MXene (EC-MXene) with no byproducts from a single exfoliation cycle are achieved.

Congratulations and thank you to our collaborators from TU Wien and CEST for very interesting work and making it published! In this work, an upscalable electrochemical MXene synthesis is presented. Yields of up to 60% electrochemical MXene (EC-MXene) with no byproducts from a single exfoliation cycle are achieved.